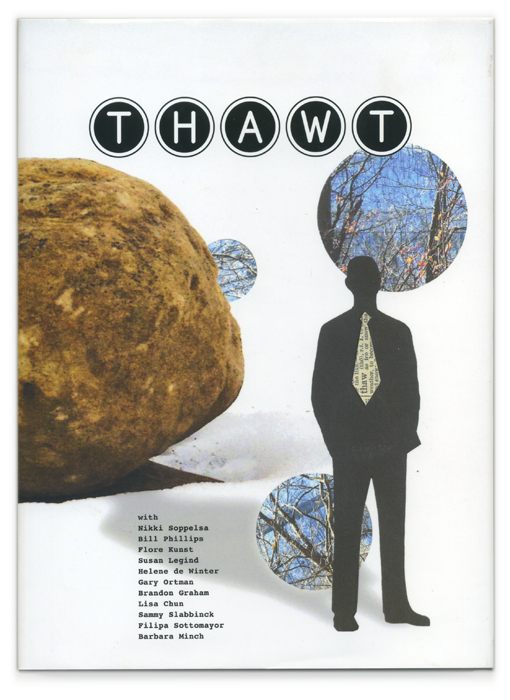

Anthology/Various Artists

2014

THAWT is the full documentation of the spontaneous 60-day collaboration between Mister Koppa and eleven other artists around the world—virtual friends invited to participate in the creation of a physical book.

212 pages (70 in full color), 24.75 x 18 cm, digitally printed on 80 lb. coated acid free paper, and case-bound with printed end sheets and dust jacket, in a signed and numbered limited edition of 40 copies, published by The Heavy Duty Press.

Collaborators include: (in order of appearance):

Nikki Soppelsa (U.S.A.)

Bill Phillips (U.S.A.)

Flore Kunst (France)

Susan Legind (Italy)

Helene de Winter (The Netherlands)

Gary Ortman (U.S.A.)

Brandon Graham (U.S.A.)

Lisa Chun (U.S.A.)

Sammy Slabbinck (Belgium)

Filipa Sottomayor (Portugal)

Barbara Minch (U.S.A.)

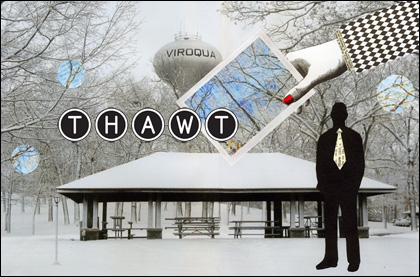

Each copy includes a signed print of the photograph by Michael Koppa, taken 20 February 2013, which inspired the project.

Thawt: noun, A period of simultaneous reflection and new growth following a freeze or hibernation, generally occurring between mid-February and mid-April in the northern hemisphere. His productive year began with a good thawt.

Thawt: book, A chronological collage of content, telling the story of a 60-day collaboration, between Mike Koppa and eleven artists and friends from around the world, during the thawing months of 2013. Thawt is a book about creativity, spontaneity, impulse, and action. The narrative is largely told through the correspondence between the contributing artists and the designer/publisher, interspersed with contributed prose, poetry, photography, and collage.

The story behind the project

3 February 2014

Here in the northern latitudes, during the months of December and January, we experience the freezing of our world as we move through a period when Earth’s axis tips us away from the direct light of our life-giving star, the Sun. We learn about our planet’s revolution when we are children, and experience it year after year for the rest of our lives, without giving it much thought. After this period of hibernation our world thaws, and we begin to grow, again and again.

This story begins nearly one full revolution ago, on a 0° day, when I gazed upon a bright blue sky through the skeletal ribs of the sleeping woods from the top of a hollow, about one mile east of the Liberty Town Hall, in southwest Wisconsin. This was shortly after the uneventful passing of the winter solstice in 2012—the much-publicized end of the Mayan calendar, and the world as we know, or knew it. To some, the end of the world marked the dawn of a new age—an “ascension” into a new collective awareness of who and what we are.

At the top of that hill in Liberty, I took a photograph. This is something people do every day. That’s what cameras do. That’s why we have them. But why do we take them? And more specifically, why did I take that one?

It was at this same time in early 2013 that I was lamenting my tendency to generate more ideas and more “stuff” than I will ever be able to address or use. I had to ask myself why I was taking photographs of those frozen woods. Sure, the moment moved me, and I wanted to have a record of being moved, but was that it? What was the real value of saving so many digital images on my hard drive for the rest of my life? Was there any value? Or was it just a growing, silent burden?

At that moment, I decided that if I was going to continue taking photographs that day, I needed to do something with them.

Earlier that week, I was at the post office to send an international letter to a collage artist in New Zealand. I met her through Facebook. The woman behind the counter held up a sheet of seven airmail stamps and asked if I sent international mail regularly. On a whim, I answered, “No, but I could.” And I bought them.

I also had recently made a decision to leave the world of social media (albeit temporarily), and instead make an attempt to engage in more personal correspondence. I wanted to satisfy a need for something more physical, and a method of communication not so off-hand and fleeting as the “status updates” I had been reading for the previous two years.

This is where it all comes together.

One valuable thing that came out of those two years of facebooking was an awareness of other collage artists around the world. Before Facebook, I never knew so many people shared a fascination with the same medium I practice. Nor had I ever had the opportunity to nurture an appreciation for the work of other contemporary collage artists, or have any kind of relationship with any other like-minded artists. I worked alone. I thought alone. Eventually, some of those artists became my new virtual friends.

“Hmm…” I thought, at the top of that hill, looking down over the frigid hollow, “What would happen if I engage with my new virtual friends in the physical realm by sharing some photographs of my experience in envelopes mailed with those seven stamps?”

And at that moment a little snowball began to roll down the hill.

A small group of collage artists I met through Facebook each received a series of photographs and an invitation to respond to them. I promised that if I received enough response from this spontaneous act to take the project further, it might become a book. Ultimately, I was able to enlist a handful of collagists from around the world, a few friends I had met through the internet in the days preceding my engagement with Facebook, and one friend from the earliest book-making ventures of this enterprise in 1996, to participate in the thawing of my frozen world—my world of isolation.

For next two months, between 20 February and 20 April 2013, my priority was communicating with a group of international artists, orchestrating and designing a book documenting this very unplanned creative effort.

At the close of 2013, I opened the files to review the unpublished book as I had left it. Here it was, cold again, as we were all preparing for the deep freeze, which we received in full as the Great Polar Vortex of 2014. And now, as the vortex leaves us, and we are moving into another highly anticipated thawing of our world, I am happy to announce the publication of THAWT, a chronological collage of correspondence, prose, poetry, and collage art, telling the story of precisely what can happen when we act on our creative impulses.